Autologous fat grafting increasingly plays a role in breast reconstruction, yet the technique is still evolving. In general, fat grafting is considered natural and flexible, which are its main selling points. An important principle for reconstructive surgeons is to replace tissue loss with a natural substitute. Given the breast’s make-up of fatty tissue, the use of autologous fat transplanted from elsewhere is in line with the basic plastic surgery principle of replacing “like with like.”

Flexibility comes into play because the contours of a reconstructed breast mound may lead to step-offs in the reconstruction. The flexibility of fat gives surgeons the ability to sculpt and reconstruct the breast so that there is a more gradual contour from chest wall to breast mound.

Fat Grafting and Breast Reconstruction: The Controversy

From unpredictable results to concerns over increased recurrence of breast cancer, fat grafting to the breast is not without controversy. Healthy scientific debate is and should be part of many topics in breast surgery, and fat grafting is no different. With respect to unpredictable results, we have generally been able to expect and deliver predictable fat grafts by minimizing the number of variables that we introduce as part of our grafting process.

Proper patient selection is the first such variable. We look for patients who are healthy nonsmokers and exclude patients with major medical comorbidities. Beyond patient selection, we minimize variance by harvesting, processing, and delivering tissue in a similar manner each time.

We harvest tissue using standard liposuction cannulas calibrated at a low setting so as not to damage the fat cells, and process tissue using a closed filtration system (Puregraft©), which has been documented to eliminate 97% of debris such as red blood cells, white blood cells, and importantly, free lipid. We deliver the fat graft using the Coleman fat grafting cannulas. In short, by minimizing the variance associated with each step, we introduce fewer opportunities for error and believe this translates into more predictable results.

The issue of cancer recurrence after fat grafting has been the subject of a number of published papers in the past several years. In 2012, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons issued guiding principles for fat grafting postmastectomy. The committee reviewed scientific evidence and found no evidence of increased recurrence in breast reconstruction patients undergoing fat grafting.

For patients who underwent breast-conserving therapy (BCT), the data continues to be collected and the risks surveyed. In a 2011 paper published in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, the investigators followed a group of 513 patients who underwent a total of 646 fat transfer procedures, including 143 patients who had BCT. With an average follow-up of 19.2 months, the authors reported the overall oncologic event rate was 5.6% (3.6% per year) and the locoregional event rate was 2.4% (1.5% per year). Many authors, including this group, recommend close follow-up in this population, which is consistent with standard of care.

For these reasons, our routine follow-up is every week postoperatively for about a month, and then we space out the postoperative follow-ups over time to every 2 to 4 weeks for 3 months, then 6 months, and finally, 1 year. While many in the

field look to metrics such as percent of fat retention as a measure of clinical outcome, our sense is that this approach may be limiting. A 50% retention for one patient may have tremendous impact, whereas a 90% retention in another patient may be inadequate.

Therefore, we ultimately look to patient and physician satisfaction as it relates to appearance, skin texture, and sensation of the reconstructed breast as our desired clinical outcomes. To be clear, we are not advocating that volume retention does not play a role. We simply see it as part of a larger equation of success.

Fat Grafting and Breast Reconstruction: Case Studies

A 45-year-old BRCA-positive woman with a strong family history of breast cancer elected to undergo bilateral prophylactic mastectomies and immediate breast reconstruction (Figure 1,

This particular woman was very thin, and did not want to use implants for her breast reconstruction. She also did not have enough tissue in her abdomen, which is usually my first choice for a donor site. Thus, I performed microsurgical breast reconstruction using tissue from the back of her upper thighs to re-create her breasts (Figure 2, upper right). This is a very elegant type of microsurgical breast reconstruction with an imperceptible scar at the donor site.

Since I use the profound artery perforators (PAP), there is also minimal donor-site morbidity with the PAP flap because the muscle is completely spared. After her breast reconstruction, however, she was still missing tissue at the superior pole of her bilateral breasts. So we did a second-stage breast reconstruction using fat grafting to fill in the defect.

With regard to patient expectations, she knew that she would have soft, warm breasts that looked natural. Since I used her legs and abdomen as the donor site for her fat grafting, she knew both would be thinner postoperatively. I let her know that she would be very bruised initially, but that the bruising and swelling would resolve.

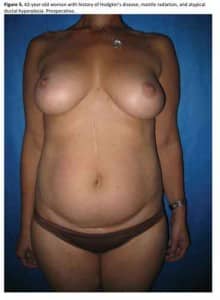

Another clinical example where fat grafting has made an important difference in terms of recovery involved a 42-year-old woman with a history of Hodgkin’s disease who underwent mantle radiation at age 18, which put her at high risk of developing breast cancer (Figure 5, below). When she was diagnosed with atypical ductal hyperplasia, she decided to proceed with bilateral mastectomies and immediate deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap breast reconstruction (Figure 6).

She developed an infection at the lateral aspect of her right breast, however, which left a slight indentation. Thus, I fat grafted her right breast to improve symmetry with the left breast . The fat grafting of the indentation at her right breast made an important impact that contributed to the patient’s overall recovery and self-esteem.

Fat Grafting and Breast Reconstruction: Clinical Pearls

Starting with the harvesting technique, I feel it is important to infuse the tumescent fluid at a low rate so as not to damage the fat cells. I also prefer to use a liposuction cannula that is 3 mm or less to minimize donor-site deformities postoperatively. Although this may take a little bit longer, it also minimizes rippling and divets that can happen with larger-caliber cannulas.

I also set the liposuction setting to 10 mm Hg to minimize damage to the fat cells. With regard to the grafting technique, it is important to make sure that small aliquots of fat graft are injected into tissue—not empty cavities—so that nutrients can diffuse by osmosis to feed the fat cells.

Fat Grafting and Breast Reconstruction: The Future

Today, there is growing evidence that enriching fat grafts with a stromal fraction may augment the viability of the graft, but this is not part of our routine practice. As discussed above, we feel that positive clinical outcomes can be achieved with careful patient selection and standard processing techniques.

Nobody has a crystal ball, so it is impossible to predict the future. Fat grafting in breast reconstruction has become more and more popular for good reason. Fat grafting gives plastic surgeons a tool to sculpt and mold tissue so that it may be possible to restore breasts that look and feel as natural and beautiful as the original.

To view all of the figures included in this manuscript, visit our October 2014 digital edition.

About the author

Constance M. Chen, MD, MPH, FACS, is a board-certified reconstructive plastic surgeon. She is currently clinical assistant professor of surgery (plastic surgery) at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr Chen can be reached via [email protected].