Fat grafting is a hot topic in aesthetic surgery circles, but who is actually doing it?

Quite a few are coming on board all the time, actually, as the techniques and technology of fat grafting (or fat transfer) grow increasingly sophisticated and accepted by the medical community.

It was not always that way. Fat grafting has moved beyond the patient safety issues that plagued its early use. In recent years—and during 2009 and 2010, in particular—we have seen the rollout of new generations of hardware devices and fat-cleaning and cell-washing techniques. Inquisitive practitioners have done important research and introduced approaches that make the use of fat grafting more practical and efficacious.

Even more recent is the pairing of fat grafting in cosmetic applications with stem cell research.

In cosmetic procedures, fat grafting has historically been unpredictable. The transferred fat may partially resorb back into the body or contour irregularities may arise. Not only was the technology of fat harvesting and cleaning inexact, but results varied widely among practitioners.

Most significant, perhaps, was the recent product launch and FDA approval of PureGraft 250, by Cytori Therapeutics Inc, San Diego, which lets the physician purify a fat graft and remove excess “graft fluid” in a controllable manner. According to the company, the system eliminates the need for physicians to have to deal with the inexact art of centrifugation of fat or other methods. The system also speeds up the time taken to create grafts.

To elaborate on the art and science behind this and other technologies, PSP spoke with Lawrence M. Koplin, MD, FACS, a plastic surgeon in Beverly Hills. Koplin’s medical training was at The Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, followed by a 5-year general surgery residency in Los Angeles prior to plastic surgery residency back in Houston.

He worked extensive on treatment of children with birth defects, multiple reconstructive techniques, and a wide range of cosmetic procedures. In breast surgery, Koplin’s specialties include augmentation, reduction, uplifts, and reconstruction following mastectomy.

He is double board-certified (in general surgery and plastic surgery), and he has been a pioneer in fat-transfer techniques.

THE ACCEPTABILITY OF FAT GRAFTING

Left: Fat grafting to lower eyelid concavities, nasolabial folds, and corners of mouth; and her 1-year follow-up (right).

At the April 2010 meeting of the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons (ASAPS), Koplin noted that the meeting’s predominant theme was about fat. There has been a sea change in that the medical community accepts the fact that fat grafting works and that it has value beyond being just a filler, he adds.

Fat grafting, he adds, “actually makes things around it look better and healthier: the skin, the soft tissues, scar tissue.”

Koplin is extremely impressed with not only the PureGraft system approach, but all new approaches that will keep the fat in a “closed system” as opposed to one that exposes the processed fat to even the OR environment, “where it can dry out and be exposed to germs,” according to Koplin.

“It works through an osmotic barrier that separates the fat from the fluids. In the other systems, everything is together in a mosh pot kind of milieu,” he explains. “Instead of mixing the fat in a bowl of saline or in a bowl of Lactated Ringer’s solution, which is more physiologic than saline, the PureGraft washes it. It’s like two rooms that are next to each other with an osmotic filtration barrier in-between them.”

The advantage of that is it allows the fat to be outside the body longer and for a safer period of time without drying out or being exposed to bacteria and outside elements, Koplin says.

Prior to using the PureGraft system, Koplin says he would place the fat “in a strainer, and pour Lactated Ringer solution and wash it at the operating table. You wash it in the Lactated Ringers through the screen of a sieve and then dry it on gauze. Then you place it into syringes and inject it.”

The PureGraft system, he notes, is for doing high-volume fat grafting or fat transfer. “If you are going to put a little in the face, you don’t need [it]. But for large volume, PureGraft is the state-of-the-art approach.”

In addition to the ASAPS meeting lectures and panels, it highlighted breakout courses in fat grafting for breast augmentation and body contouring. “It was just obvious to everyone that it is going to be a permanent part of plastic surgery from now on,” he says.

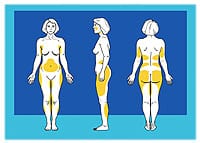

One of the big questions at the meeting, he continues, was from what parts of the human body does one harvest the best-quality fat?

“There is no answer to that yet. I personally think that the place that is the most difficult for the person to lose weight from is the best fat to use, but with the proviso that this is for small volume. I do facial fat grafting,” he says, adding that he does five to 10 per week. “I do it with almost every liposuction I do. I ask them if they want me to put a little in the face, and they always do. I do a tremendous amount of fat grafting to the face. For the face you don’t need giant volumes of fat, so you can take it from one place.”

In patients who are having body contouring, body augmentation by fat only, or breast augmentation, as well as buttocks augmentation or other areas, fat is taken from a lot of places. “You need more, too much. The one place, the tummy or the outer thigh or the hip isn’t going to be enough,” Koplin says. “We wind up doing a generalized liposuction on that person because we need 1,000 ccs of fat to process and purify and inject. With that person, there is no best place; it comes from everywhere we can get it. The by-product of that is that they get a fantastic liposuction, as well as use that fat for wherever we are going to create the augmentation.”

PUREGRAFT AND STEM CELLS

According to information released by the manufacturer, PureGraft helps physicians to prepare fat for reinjection within about 15 minutes. We asked Koplin if that statement is accurate.

(Above, top) Fat grafting correction of irregularities of upper and mid-sternum; and the patient’s 8-month follow-up (above, bottom).

“Yes. There are things that we are, as plastic surgeons and as investigative plastic surgeons, trying to do to make the fat [richer]. But in actually cleaning the fat and preparing it for grafting purposes, I think that PureGraft is the most elegant and safest way right now that we have,” he says.

Physicians may want to take the processed fat and go several steps further, such as try to make it more stem cell concentrated or more stem cell rich. In any case, one wants to wash the fat first and get rid of the extra fluid first, Koplin adds.

When working with stem cells, you have to get the stem cells first, he says. “There are two current philosophies as to how to do that. One way is to centrifuge the fat; and there are several very smart clinicians and researchers that have shown that if you centrifuge the fat then you can create a more stem cell-rich part of the fat. The part of the fat in the centrifuge portion has more stem cells than another part of the fat. And some of them do that without using the Pure Graft system and they don’t wash the fat. They purely centrifuge it.”

In Koplin’s view, it is better to create the clean, protected fat and centrifuge it later to create that stem cell-richer segment. “You have a more pure product,” he explains. “You have actually washed out, rather than centrifuged into separate areas, the blood, the local anesthesia, and the oil from the injured fat cells. You centrifuge the fat to create the stem cell-richer segment. I think that’s a better way of doing it than using the centrifuge to do all that at the same time.”

Another approach will be Cytori’s upcoming CellGraft product, which will be similar to its earlier Celution System in size, but on top instead of a centrifuge will be a seesaw-like device that will inject saline solution plus enzymes to digest the fat and prepare its output for cosmetic surgery applications. These machines, which are certified in Europe but not in the United States, are eagerly awaited by US-based physicians. Also, this approach creates a very small amount of stem cells—a teaspoon, Koplin says, containing no fat cells.

TECHNICAL MATTERS

On a day-to-day level, how does the system work and how does it make your procedures more efficient?

“It is a little slower,” Koplin admits, adding that the PureGraft system is intended for use in larger volume fat-transfer procedures. “Not just for a little bit of things in the face, but for major facial reconstructions after trauma or for a person who has had a lumpectomy after a mastectomy, and they have a big shark bite out of their breast. You can’t fix that with an implant because an implant is just going to make a bigger breast that has a shark bite in it. You need to put something right in the dent, and the absolute best thing to use is fat.”

Koplin expects manufacturers to produce more systems similar to Pure Graft, systems that “would not only do liposuction but also take the fat out and process it for fat grafting,” he says. “The more the public reads about it in the lay press, the public is going to clamor for it because it’s so much better than implants and it’s so much better than fillers. Don’t get me started about facial fillers. I am not a fan because fat is much better. It looks like what it’s trying to be, which is fat. Also, they are temporary. Why lease something when you can buy it?”

What kind of negative outcomes are possible for this approach? Patients “can’t have a bad reaction to fat,” Koplin says, “unless you are putting in fat where there is a high amount of impurities, because it hasn’t been washed properly. Or, a lot of the fat is dead and you are injecting dead fat cells. It could have been bacterially contaminated and you are running a risk of infection.”

(Above, top) Hand rejuvenation using fat grafting to fill hollows between extensor tendons and to camouflage prominent veins; the patient’s 10-month follow-up (above, bottom).

The newer, cell-washing technologies, including PureGraft, address those risk factors in a safe way, Koplin adds.

FAT GRAFTING IS IN

“I am a huge believer in fat grafting, and I have been dong it for over 20 years,” Koplin says. “Since I started taking fat out, I have been putting it back in. I have been watching this evolution. And up until about 3 years ago I would ask colleagues, ‘Hey, are you fat grafting with your facelifts?’ And they would go, ‘That’s ridiculous, it doesn’t work. It’s a waste of time. No, of course I don’t do it.’ ”

Some plastic surgeons that have talked about it in meetings and in the public forums have been ridiculed at times, he says, adding that the work of Sydney Coleman, MD, has made a big impact on the improvement and advancement of fat grafting.

“He took really good photographs and medical records, and took the time to write about it,” Koplin says. Coleman showed photographic proof over time, he adds. “Not just a month but a year later and 5 years later. Finally, it’s become acceptable. I don’t really know why now except I think that people are kind of getting tired of all these fillers. There are a hundred different fillers. How many Botoxes are there? There’s one. Now there is Dysport, so there are two. There aren’t a hundred. Why? Because they are great products, there are basically no side effects, they work, and there’s nothing better. There are a hundred fillers because none of them are all that great. Otherwise, there would be only two.”

Why have physicians not been doing fat grafting instead of using fillers?

“Because doctors make more money doing fillers,” Koplin says. “You can do 20 to 30 patients in a day doing fillers. You sit them in a chair and 10 minutes later they give you $1,000 or $2,000, and they keep coming back. The second reason is that it is an artistic challenge to do fat, because you don’t just fill in a line. You can makes lips prettier. And you don’t just throw the fat in, you actually decide, ‘Well, do I want the outer part of the lips? Do I want the middle part of the lips to be fuller? Do I want to roll them out? What’s the balance of the ratio of the upper lip to the lower lip? Am I am going to make the cheekbones fuller?’

“I can actually reshape the face. When you have that power, it becomes scary because you are no longer filling wrinkles—you are truly sculpting in three dimensions. I think a lot of plastic surgeons are not totally comfortable with that. And there is a learning curve [that] some people don’t want to jump into.”

Plastic surgeons can respond to customer desires to move away from using fillers and using more of his or her own fat, Koplin says. “Some really good surgeons are showing fantastic results with the combination of facelifts and fat grafting, and they are showing some fabulous results from breast enlargement and breast reconstruction using fat grafting.”

He says the next generation of issues will be, if you put stem cell supercharged fat in the breast, will there be any possible negative consequences?

Janine Ferguson is a contributing writer for PSP. She can be reached at [email protected].

Lawrence M. Koplin, MD, FACS, reports he has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

FAT GRAFTING IN BRIEF

Although the popularity of fat grafting has recently increased substantially, it is not a new surgical technique-—it began as early as 1893 with free fat autografts that were used to fill soft-tissue defects.

Throughout the 20th century, physicians used fat grafts to correct many conditions, including hemifacial atrophy and other soft-tissue defects. Because of recent advances in technique to improve graft “take,” along with growing media attention, fat grafting is more popular than ever.

Techniques have been refined from the 1980s, and now the fat to be used for grafting is carefully removed with a syringe and is processed minimally. The fat is then grafted in thin strands, and a lattice is constructed to correct a wrinkle or restore volume to a specific area.

Fat-handling techniques have improved, but multiple or staged procedures are still the norm. Despite the possibility of requiring retreatment, fat grafting compares well to other soft-tissue fillers.

—Henry A. Mentz, III, MD, FACS, FICS, and Amado Ruiz-Razura, MD, FACS, FICS