Beauty CULTure, a photography exhibit about beauty, was among the biggest draws in Los Angeles over the summer. Sponsored by the Annenberg Space for Photography, it opened a discussion of contemporary notions of feminine beauty by showcasing world-renowned fashion and fine art photography. As visitors milled around the tasteful Century City exhibit space, its walls studded mostly with photographs from the fairy-tale worlds of haute couture and Hollywood, a half-hour documentary played on endless loop in a central arena.

One theme that emerged was that fashion and movies have sold the American public unattainable visions of beauty, visions that women are tied up in knots trying to live up to. This is not the most original thought they could have come up with. In fact, the tread has worn pretty thin on this insight. Cosmetic surgery, of course, was seen to play a part in this infernal scheme.

The aesthetic profession fared poorly in this show, and particularly badly in the documentary. You appear in a segment that also features a female bodybuilder who looks and talks like a transsexual, a toddler gussied up for a beauty pageant, and someone who had silicone facial implants inserted above her eyebrows to protest the excesses of plastic surgery.

Other well-worn clichés of anti-cosmetic-surgery make their appearance, too: a photo of a woman sitting on a bed the day after facial surgery, bandaged up like a war victim; images of old faces straining for Brigitte Bardot-like sensuality; wind-tunnel-cheeks and hatchet jaw lines from circa- 1965 plastic surgery; lip augmentations taken to freakish extremes.

The denouement came in the documentary when narrator Jamie Lee Curtis tried to sum up plastic surgery’s role in our society by calling it “genocide.”

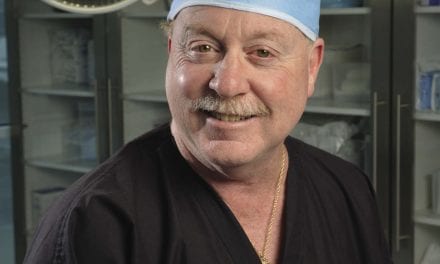

SAYAH’S TAKE

“For every overdone face like the ones they show in this exhibit, there are hundreds of women out walking the streets with beautiful results no one can detect,” says David Sayah, MD, a Beverly Hills-based plastic surgeon who attended the Beauty CULTure exhibit with me.

“I wonder why the curator selected these,” he pondered as we passed through the first part of the exhibit, an intimidating gallery of supermodels and famous actresses. “To represent what is beautiful, or to ask us to question why we as a culture see this as beauty?”

He stared at a 60-year-old Elizabeth Arden magazine ad. The model’s hair and make-up were dated but she had the same perfect complexion and pronounced lips as more contemporary models directly across the aisle from her. “You can see how ideas about what’s beautiful evolve,” Sayah says, observing similarities among the images.

“As beautiful images like this one are disseminated and resonate with people, they’re selected out and repeated. Soon the qualities they promote are assumed to be requirements for beauty. Beauty Is Subjective, but in truth there’s no objective measure of beauty,” he reflects. “Things that are beautiful in one culture are ugly in another. That’s why it’s important for plastic surgeons never to impose their ideas about beauty on their patients.”

As we passed through the gauntlet of exquisitely presented women, Sayah was sometimes visibly moved. He clearly loves beauty. (He’s a fine artist when off-duty from surgery and family activities.) We walked past a series of photos of Marilyn Monroe before she’d became an erotic icon. The famous calendar-girl image of her as a slender, lissome teenager with honey-blonde hair and a fresh smile was achingly innocent, despite her nakedness. “What a tragic fate,” he murmured as we passed.

We arrived at the central arena where a few dozen people were sitting on oversized ottomans watching the documentary. We stood and listened as cosmetic surgeons were fingered in a dastardly scheme to cheat women of their right to untrammeled ideas about beauty.

After the documentary was over we went outside to a windy courtyard and sat at a table drinking coffee. “Did that documentary bother you?” I asked. “Do you think it was unfair to select only the ‘train wreck’ images of plastic surgery? Were you insulted by the genocide comment?”

“I don’t take it that seriously,” he replied mildly. “Those are all just clichés by now. A word like ‘genocide’ gets attention because it’s sexier than talking about the real issues in plastic surgery, like improving safety for patients. I’m not surprised to see the show pandering to a tabloid mentality. It’s what sells newspapers and museum tickets. It’s what gets ratings.

“The people with beautiful, natural results – the majority of cosmetic surgery patients — they’re the silent majority. They’re invisible on the street so they’re ignored.”

I tried something more plausible: “Do you think plastic surgeons take advantage of the unattainable standards of beauty we’re exposed to?”

He thought for a minute. “It’s more like….we are in the middle of a dynamic. People want to be beautiful. They want to be accepted. They strive for beauty and social position and the admiration of others. That’s just human nature, you can’t change that. It’s been going on since human society began. Cosmetic surgeons have skills people can use to try and reach those goals.” If you regard those goals as unholy, cosmetic surgeons are part of something you don’t like.

“There’s no sense trying to talk people out of their own human nature,” he commented. “It won’t work. Then the only question is, ‘How far are people willing to go to gain acceptance or move up in the world?’ And that’s where our moral obligation as doctors comes in. How far patients decide to go in changing their faces or bodies is up to them, but we have a responsibility as doctors to counsel them. To make sure the decision they make brings the best outcome with the lowest risk.

“When we do plastic surgery we expose people to risks. They are perfectly healthy before we expose them to those risks, so as medical practitioners we have a moral obligation to advise them in a way that lowers risk. This is what we talk about at our meetings among ourselves. How can we make cosmetic surgery safer? How can we make it last longer so it doesn’t need to be repeated? None of that was mentioned in the show. Those are the interesting questions,” he says, not the bread-and-circuses side-shows.

STANDARDS OF BEAUTY

Plastic surgeons also have an obligation not to exacerbate the standards suggested by fashion, media, and all the tastemakers who have access to the public’s consciousness.

“The only standard of beauty I impose on my patients is that they respect the role health plays in making people beautiful,” Sayah says. “You can’t expect to get plastic surgery and suddenly be beautiful if you are smoking, if you’re overweight, if you dress like crap. I have a personal trainer and a nutritionist on staff at my practice, and I insist anyone who comes to me for cosmetic improvement work with them first. They have to give healthy living and exercise a chance before I will work with them.”

In his view, today’s lifestyles don’t promote optimum beauty. Mainly, people don’t move enough in our sedentary world. Correcting this error often brings results that amaze his patients. They thought they were in decline. They had no idea how much natural fat loss, exercise and the right nutrients, hormones and enzymes could do to restore their natural beauty.

“Once they reach a plateau where healthy habits no longer bring improvements, then I will consult with them about making improvements through surgery.

“The other day, a woman came in to consult about nose surgery and I looked at her and said, ‘You’re absolutely beautiful, and there’s nothing wrong with your nose. Why do you think you need me to ‘fix’ your nose?’ This kind of thing happens a lot in my practice. I love telling my patients, ‘You can come back as many times as you like and if I see you 20 times and you finally decide surgery is not what you want, that’s OK. I still will have done my job.’ I define my job as making people feel more beautiful. If I do the surgery and my patients don’t feel more beautiful, then I haven’t done my job.”

The afternoon was getting late. Sayah was eager to return home to his wife and 2-month-old baby girl. As we exited the café, helicopters still patrolling noisily, Sayah turned to me. “Our ultimate goal as surgeons should be to have people feel better about themselves, with or without plastic surgery,” he notes.

Beauty CULTure will remain at the Annenberg Space for Photography, 2000 Avenue of the Stars, Century City, Los Angeles, through November 27.

Joyce Sunila is the president of Practice Helpers, providing e-newsletters, blogs, and social media services to aesthetic practices. You can contact her at .